Research shows the disappearance of a species is happening in Missouri’s backyard, and it doesn’t look like it’s getting any better.

Assistant professor of biology, Dr. Aaron Geheber, recently received a $109,305 grant from the Missouri Department of Conservation to discover where Missouri’s remaining Topeka shiners live.

The Topeka shiner is a small fish, the size of a minnow, that is nearing extinction due to pollution and chemical run-off in Missouri streams.

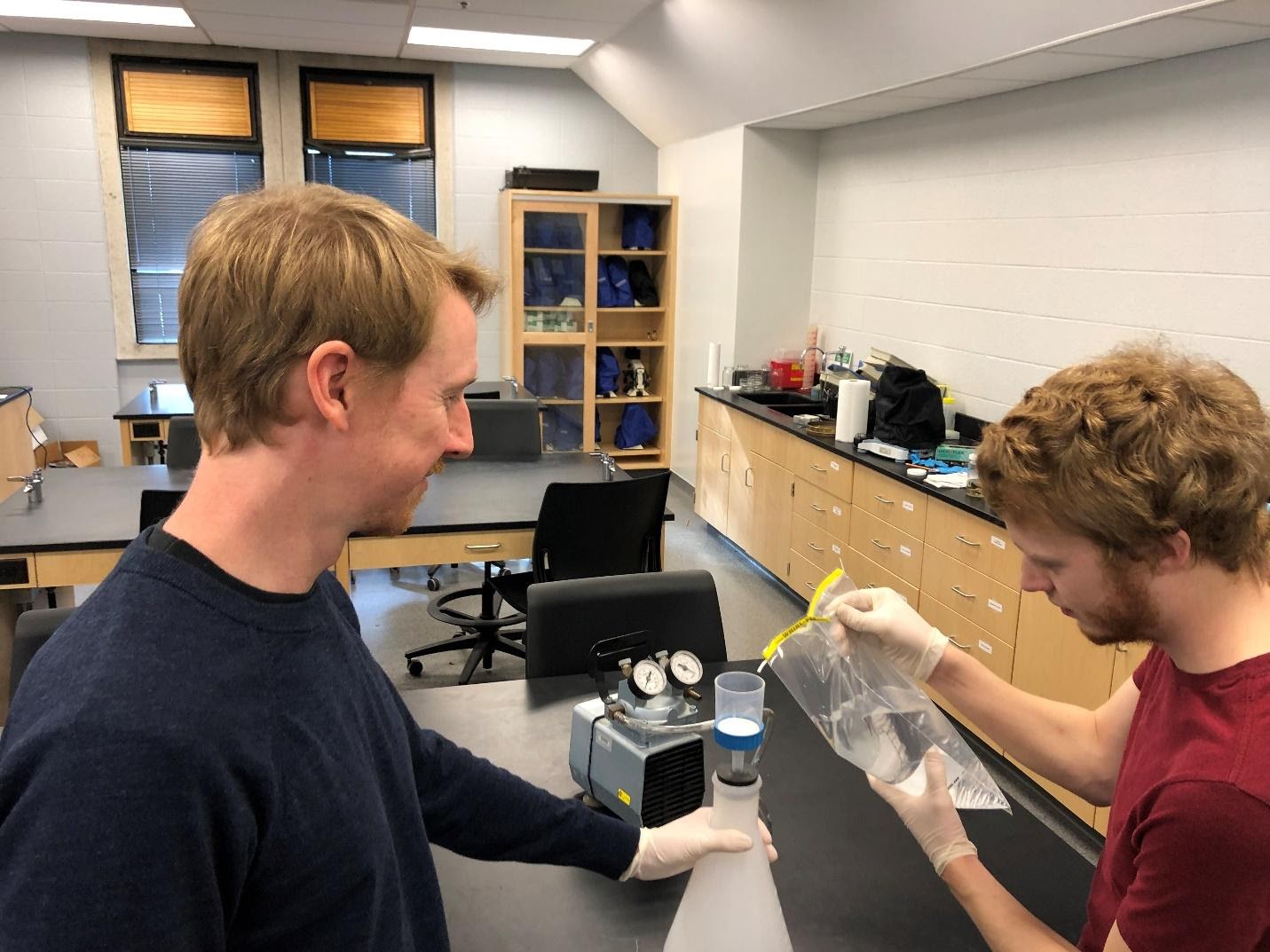

With this grant, Geheber is using a new environmental DNA (eDNA) technique to find the shiners by sampling waterways across the state and extracting the species’ DNA.

The Missouri Department of Conservation grant Geheber received states it covers, “field supplies, travel, lab supplies, and graduate research assistant support for three years.”

Geheber’s graduate assistant, Austin Mueller, said he is excited to help for the next couple of years.

Mueller said, “My interest is in endangered species; just kind of getting out there and seeing the rare and being able to get on it before [these species] become extinct.”

Mueller moved to Warrensburg from North Carolina to work with Geheber. Using the Texas A&M job board, the graduate (student) applied to help with Geheber’s research.

“It was a wide recruitment, I even had international students apply,” Geheber stated about the applicants, “We interviewed and then I guess the rest is history.”

Geheber said he accepted applications from students all over the world interested in the project, but Mueller was the best fit for the position.

The research was prompted by the rapid disappearance of the Topeka shiner.

100 years ago the Topeka shiner was a very common species, now it can only be found in a select few places. Geheber believes that the cause for this decline is mainly due to agriculture.

The decline was a big red flag to both Geheber and the Missouri Department of Conservation.

Geheber said he hopes that the state will be able to use their research to help identify where the shiner is today, then use the eDNA technique as a tool in the future to detect other threatened or endangered species.

Though eDNA technology has been around for a while, Geheber and Mueller will be some of the first researchers in Missouri to apply the technology.

“This is something that has been used pretty readily now for the past 20 years,” Geheber said, “[but I] think we’re bringing the methodology to something that is applicable here in the state.”

Geheber’s research is important to help find the Topeka shiners, and also to pioneer the use of the eDNA testing process in Missouri.

The field research will take place in two main regions of the state where the Topeka shiners are believed to inhabit.

The first area will be in northwest Missouri, and the second in central parts of the state.

Geheber plans on finding where the Topeka shiner remains and how many are left in those places.

The Topeka shiner has lost more than 90% of its original habitat due to pesticide runoff, fertilizers, and other agricultural waste that gets dumped in the water. Without clean water the Topeka shiner cannot survive due to its inability to adapt to sudden change.

Both Geheber and Mueller believe that there is something larger afoot causing the rapid decline in this species, but don’t have any solid evidence as of right now.

At the beginning of this year, President Donald Trump repealed a portion of former President Barack Obama’s 2015 environmental legislation, “Waters of The United States.”

This legislation protected all streams, rivers, creeks, and other bodies of water, and controlled pollution and harmful chemicals being dumped into the water.

Geheber mentioned he doesn’t think repealing the Clean Water Act is good for any aquatic organisms, or us humans.

Starting in March, Geheber and Mueller plan on heading out to the field to begin gathering research. For the next month, Geheber and Mueller will be indoors, planning for the busy spring and summer that follow.

Leave a Reply